Chicago Greens

Next monthly meeting on Sunday, March 8th, from 2-4:00 PM, at Powell's Boostore, Halsted and Roosevelt (800 W, 1200 S)

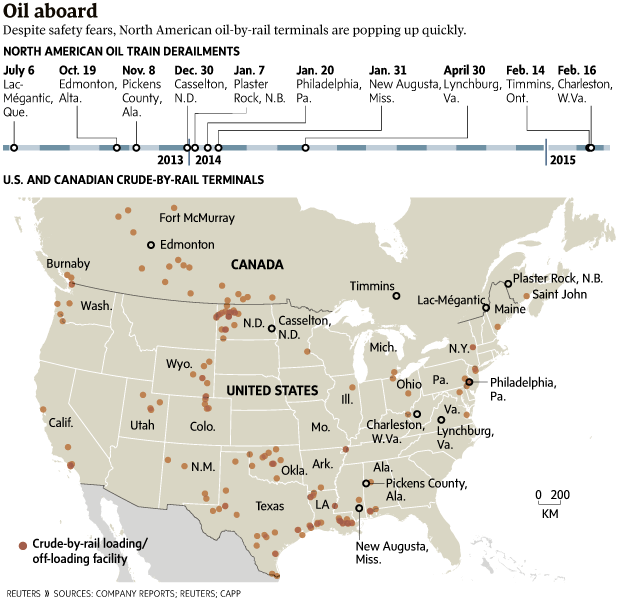

Oil train derailments reignite debate over railway safety rules

Eric Atkins - Railway Industries Reporter

The Globe and Mail Link to Article

Published Tuesday, Feb. 17 2015, 7:09 PM EST

A pair of recent oil train derailments and fires involving upgraded tank cars have raised fresh questions about the safety of moving crude by rail.

Trains hauling oil crashed and caught fire in Northern Ontario and West Virginia on Sunday and Monday, respectively. In both cases, the railways said the tank cars were the newer style, known as CPC-1232, with thicker skins and shielding over valves designed to prevent spills and fires in a derailment.

More Related to this Story

Emergency crews and environmental officials are responding to a train derailment in West Virginia that sent at least one tanker containing crude oil into a river and also caused a nearby house to catch fire. (Feb. 16)

Requiring oil shippers to use the upgraded models and phasing out the older, more spill-prone tank cars by early 2017 is a central part of Ottawa’s response to the 2013 explosion in Lac-Mégantic, Que., that killed 47 people.

The amount of crude moving by rail has soared in the past few years amid a shortage of pipeline space that has oil shippers looking for new ways to reach refineries. Oil and related products account for almost 10 per cent of revenue at Calgary-based Canadian Pacific Railway Ltd. At Canadian National Railway Co., the figure is believed to be closer to seven per cent, but the company does not say.

Both railways are expected to move a combined 340,000 carloads of oil this year, even amid a crash in crude prices that has dampened growth.

The Railway Association of Canada, which does not comment on incidents involving members, is calling for tank car standards that surpass those currently imposed by Ottawa.

The industry group says it expects Ottawa and the U.S. regulator will address the need for tank cars with an extra layer of steel, and better protection at the front and back to prevent couplers from puncturing tanks in a crash.

A spokeswoman for federal Transportation Minister Lisa Raitt said Wednesday that the government is working with the U.S. on a “next-generation standard” for rail cars that carry flammable liquid that would be more robust than the CPC-1232 model.

Since new regulations came into effect after the Lac-Mégantic disaster, there have been several oil train crashes and fires, including the CN Railway derailment near Timmins, Ont., early Sunday, and the burning CSX Corp. crude train that caused the evacuation of hundreds of people in West Virginia on Monday.

“It’s troubling. You’ve got such an increase in the transportation of oil moving by rail and yet you still don’t have the question of the means of containment under control,” Bruce Campbell, executive director of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, said. “These accidents continue to happen, and it’s really troubling that these cars were either new cars or cars that were retrofitted. They still puncture when they derail.”

At the same time, Ottawa has cut the budgets for the inspectors who monitor railways and the goods they ship, Mr. Campbell said, and no one is talking about limiting the amount of oil moving by train.

The Bakken oil field in North Dakota is a large source of the rise in crude-by-rail shipping, as the region is underserved by pipelines. The unmanned train that exploded in Lac-Mégantic was carrying Bakken oil, which is known to be highly volatile.

The CSX train was hauling Bakken oil on Monday when it derailed in a snowstorm and caught fire.

In the CN case, Rob Johnston of the Transportation Safety Board said investigators are focusing on a broken rail and damaged wheel on a newer tank car, which CN says was one of 100 carrying diluted bitumen from Alberta.

The rail industry has estimated there are more than 90,000 of the older style tank cars hauling dangerous goods in North America, versus about 14,000 of the upgraded versions.

Mike Sullivan, an NDP Member of Parliament who sits on the transportation committee, said there are varying standards of the upgraded tank cars, and manufacturers are in no hurry to flood the market with new ones until governments in Canada and the United States settle on a common model.

Ali Asgari, a professor who specializes in emergency management at Toronto’s York University, said the focus needs to be on preventing or reducing derailments by running shorter trains that carry lighter loads, which runs counter to the industry trend of moving oil in so-called unit trains of 100 cars or more.

“It doesn’t really matter what type of car you have, derailments still happen,” Mr. Asgari said by phone.

Railway executives have said they are happy to see the end of the DOT-111s, dismissed by some in the rail business as canola cars because they are also used to ship vegetable oil. Railways are charging more to pull the older cars, but note they have no choice but to haul what the customer provides.

In response to the Lac-Mégantic tragedy, Ottawa imposed lower speed limits on oil trains and imposed new handbrake rules for stationary trains. The older cars that have not been upgraded are banned in Canada after May, 2017.

But two key issues remain unaddressed: the volatility of the oil being shipped, and routing trains hauling dangerous goods around heavily populated areas.

Railways in Canada say it is not possible for trains pulling dangerous commodities to avoid heavily populated areas, given many towns and cities were built around the railroads.